For anyone diving into football tactics, getting a grip of the 3–3–1–3 is a temptation that is hard to avoid. After all, it was popularised by an unorthodox Argentine nicknamed El Loco who, many top managers like Guardiola, Sampaoli and Pochettino, regard as their mentor and the greatest coach of the game ever.

It’s a hipster tactic. It screams in the face of conventional formations in modern football. When teams pick a safe strategy with which they can park the bus, the 3–3–1–3 looks like a jet plane. You rarely find guidelines to play a 3–3–1–3 during your coaching pathway. Anything if at all would be found on the internet written by some FM geek who experimented with it or self-proclaimed tactical buffs like me. At this point, however, I admit that I actually know very little of it despite having been obsessed with it like everyone else.

I gave it a practical shot myself in my early days of coaching a women’s team few years ago. It was a cup quarterfinal against a team that plays in the UEFA Women’s Champions League and I felt adventurous. There was nothing to lose. The game was open, end to end. But by half time, my pivot (and my best player) was fuming in the dressing room: “This is a disaster, I feel completely outnumbered in the middle and I can’t find one key pass. Our defence is all over the place.”

After watching Klich against Southampton this Tuesday, I can imagine why. Bielsa has unleashed the 3–3–1–3 at every club he’s been since the very first game — Bilbao, Marseille and Lille. But at Leeds where he has served the longest of all, he took a more cautious approach since the beginning with the 4–1–4–1 being his stock formation for most of this time in Yorkshire. The few games in which he has used the 3–3–1–3 has been a palpitating episode to say the least for a Leeds fan.

3–3–1–3 Overview

The 3–3–1–3 employs:

- 3 centrebacks that stick quick close to each other,

- 1 central midfielder that roams around in the space in front of the defence,

- 2 highly mobile and versatile wingbacks that take up any role depending on the phase of the attack and

- the attacking unit, enganche y tres puntas comprising of one creative attacking midfielder behind one central striker and two wide wingers

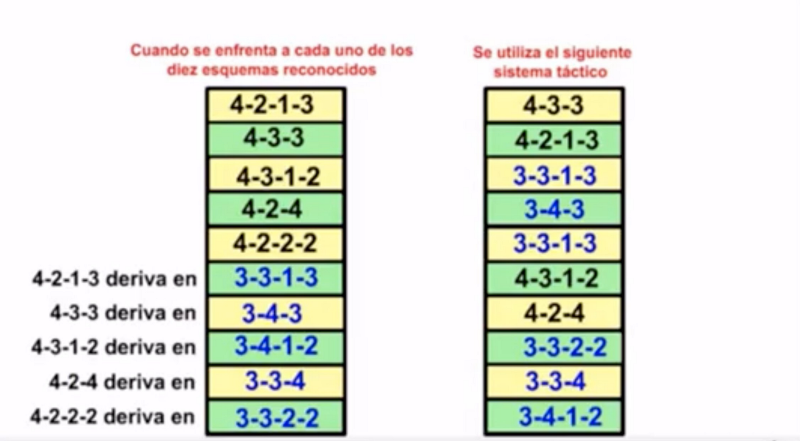

From Bielsa’s presentations, it is clear that he chooses the 3–3–1–3 formation against two opposition formations, the 4–3–1–2 and the 4–2–2–2. The mathematical reasoning behind this choice is known only to him, but the decision to have one more defender than the number of opposition strikers makes sense. Both the formations by the opposition use 2 strikers, so having 3 defenders gives immediate numerical superiority while building up play from the defensive third.

So far this season, he has used the 3–3–1–3 twice before Southampton, against Burnley and Sheffield United. Both games were played with close margins, with Leeds winning 1–0 and 0–1 respectively. In the game against Southampton Leeds secured a triumphant 3–0 win, although Bielsa claimed in his press conference post-game, “The margins were closer than what the result suggests.”

Attacking organization

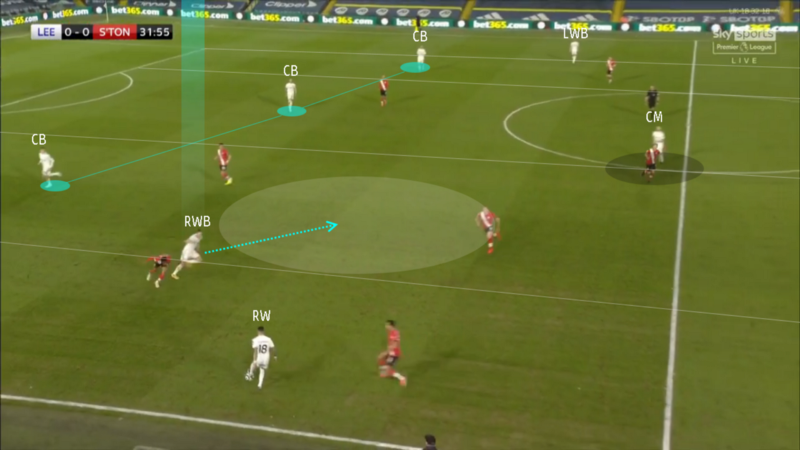

The centre forward is the focus of every attack in this system due to the lack of density of players in the middle. The first phase of buildup coming out of the keeper is straightforward and based on numerical superiority. The defensive flat back-3 provides sufficient width to deal with the press from the 2 strikers. The following three phases of buildup — construction, creation and finishing — however, are quite direct and follow rapidly. The reason is that the outlet out of the first phase to bypass the first line opposition pressure is only via the wingbacks.

The central midfielder in front of the defence is often either tightly marked or finds himself in a position of heavy inferiority. Hence, progression to the construction phase is initiated by the wingbacks either directly by a pass, or indirectly by starting a third-man run. As the play moves outwards from deep, the opposition finds it easy to apply high pressure forcing the play wide since there are no options back into the middle. The wingback is forced to make a quick decision.

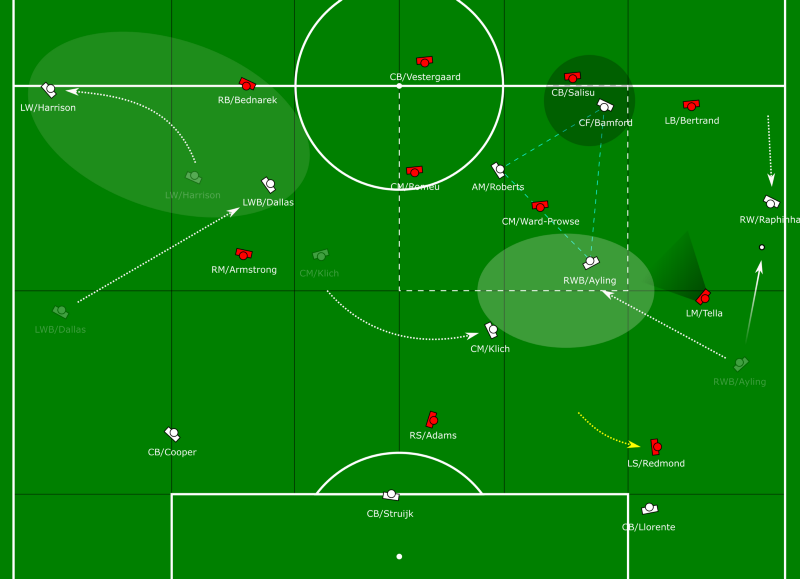

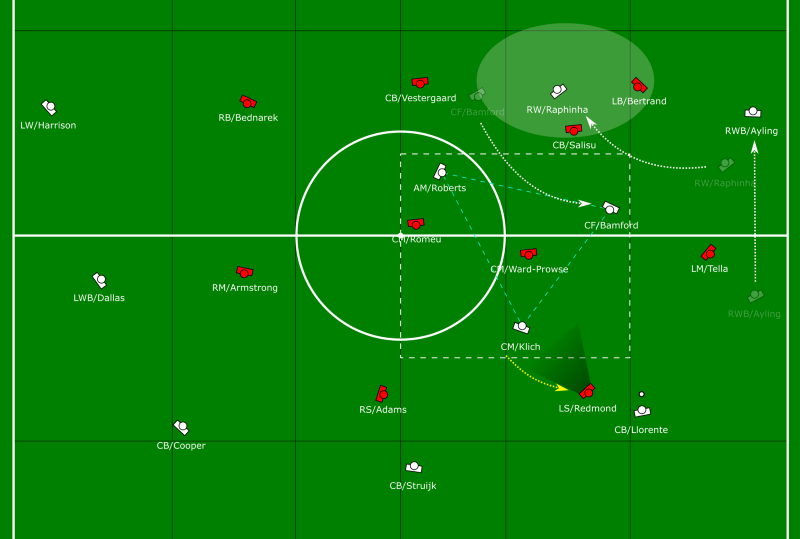

An experienced utility player like Ayling or Dallas is able to play the pass quickly forward in the same lane to the winger ahead and cut inside into the half space. By beating the wide player pressing with a quick one-two pass, the wingback now creates an overload in the half space along with the centre forward and the attacking midfielder. The central midfielder now has time to cover defensively in case possession is lost.

Simultaneously, on the opposite flank, the other wingback can drift inside forward with the winger staying wide and create a 2v1 against the opposing fullback. This movement pins the defensive back line and forces them back, but it needs to be played quickly and the switch immediately. The players need to mobilize rapidly and attack the spaces in front. A miss pass or interception by the opponent midfielders risks a 4v4 turnover with the 3 centrebacks left isolated to manage the defensive line themselves.

Superiority in the middle can also be created by the forward dropping deep. An extra player in midfield provides support to the central midfielders. The winger can now attack the space left by the centre forward and the wingback can overlap to pin back the fullback and overload the same side. Once again the ball needs to be played directly without spending too much time in the middle with short passes. Most often we see direct balls and quick plays into the final third in the 3–3–1–3 system. In the game against Southampton, Leeds had 55 long balls and 277 short passes versus Southampton’s 38 long balls and 337 short passes. Leeds also had lesser percentage of possession.

It is important for the attacking midfielder to be positioned between the lines up ahead and not play too deep. This is probably why the 3–3–1–3 can be differentiated from a regular 3–4–3 (like the one used by Conte at Chelsea) because the latter makes use of a double pivot in the middle with the two midfielders playing more box-to-box and covering greater combined area in the centre.

When the attacking midfielder plays between the lines he can always function as a third-man off a direct ball to the centre forward. When he receives the pass, the defence is forced to step back to secure the spaces behind them. This buys him time to turn and look to switch play. If the wingback on the opposite side pushes up and inside to support, along with the winger they create a 3v2.

The centre forward and the winger on the other flank can pin back their markers with runs in behind and this gives space for the wingback on the other side to make an overlap giving the player on the ball options to attack from both sides. At the end of the finalizing phase, the team has width as well as players in the box to finish from a cross. We see the dynamic versatility demanded from the wingbacks who are required to function as either midfielders or wingers depending on the situation. This explains how Dallas created the opportunity to score the second goal for Leeds against Southampton in this game.

Defensive organization

The moments of transition are quite intense in this system. The priority of defensive organization is to delay and win the ball back as soon as possible. The more time the opposition is allowed on the ball in the centre, the greater the risk of conceding shots on goal. Illan Meslier needed to have a good game to keep a clean sheet against Southampton. He made 5 crucial saves which is greater than the average of 4 saves he makes per game.

Leeds’ man-to-man marking is the hallmark of the defensive organization. They close down all options in the middle, and the centre forward and wingers cut passing angles using their cover shadows. In this system, if the opposition creates a free man in the middle, one of the 3 centrebacks needs to step out of his line to close down the player.

Timing plays a big role here as to make this decision, the centreback needs his wingbacks to be in place to cover the backline. With the wingbacks always in transition, there is always a risk of running a scenario of inferiority against the backline as the opponents counter attack.

If you notice in this instance, Leeds have all men marked in the middle and in order to create this man-to-man marking, Struijk, the centreback has to also step up and pick up a free man. Then, the left winger and centre forward are able to cut passing lanes and force the play back to the goalkeeper. The vulnerable points of the 3–3–1–3 structure are always the spaces right in front of the defence and the spaces left behind by the wingbacks pushing forward.

Lack of central stability

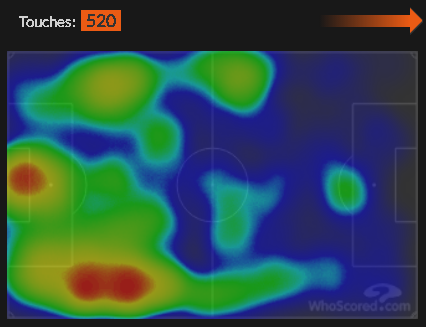

An understanding of the system from the previous sections provides a hint as to why the 3–3–1–3 lacks central stability. If we look at the heatmap against Southampton we see a U-shaped occupation of the area around the 18-yard box in Leeds’ own half.

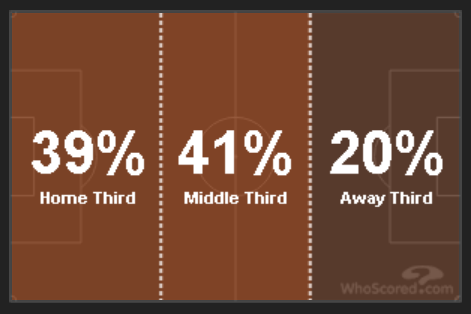

But the crucial areas in the middle around the centre circle are empty. For a possession based team, it is crucial to control the centre of the pitch and this explains why Leeds have lesser possession than usual in the 3–3–1–3 system. It is a formation better designed for direct play.

Leeds also spent a lot of time trying to build out of from wide areas in their own half using their wingbacks to progress into the next phase of attacking organisation. A central pivot who is primarily assigned as a defensive midfielder like Kalvin Phillips holds responsibility of constructing the attack after surpassing the first line of pressure.

We can clearly notice Phillips’ absence especially looking at the areas of occupation. In the touchmap above, notice how the 3–3–1–3 tends to dominate play along the wide channels and in deeper areas. We see a lack of density of touches along the half spaces or inside channels. The 4–1–4–1, with a second row of four, also helps control the centre better and it is impossible for the single enganche to dominate the space around the centre circle in the 3–3–1–3 system.

The two central players, Klich and Roberts had in fact, the least number of touches in the team during the game (Harrison was substituted at half time). Klich usually averages a pass accuracy of 82% but in this game he only managed 13 accurate passes out of 19 with a pass accuracy of 68%. The central players have very little time to make the right decision, always having to play in numerical inferiority and need to play the right pass in two touches at the most.

Roberts’ assist to Bamford for the first goal was played with the second touch, almost falling off balance attempting it. The central midfielder in front of the defence is simply overwhelmed by the area to cover as a box-to-box player. Without constant support from the wingbacks, it’s nearly an impossible position to play, and the wingbacks always need a certain cue from the opponents to decide their move. It is no surprise now why my pivot was left helpless at half time when she played this position, despite the attacking opportunities created.

3–3–1–3: conceptual or practical?

The success of this system relies on the ability to be brave and dominate the wide lane despite being pressed to the touchline. The linear stack of three players in a narrow lane need to engage in dynamic rotations to overcome opponents one by one. Bielsa’s four core principles: concentración, permanente movilidad, rotación y repenitización (concentration, permanent focus, rotation and improvisation) echoes louder than ever in the 3–3–1–3.

The risk-reward ratio is also pretty even, especially in transitions as you can have a 4v4 in attack than can soon turn into a 4v4 in defence. The absence of central players to provide defensive stability is the reason. It makes sense why Bielsa attested to the margins between the two sides being fine despite the result. The disconnect between attack and defence only gets bigger once the central players and wingbacks experience fatigue. In terms of periodization, playing a 3–3–1–3 in a competitive league every week is sure to result in burnout eventually.

Nevertheless for tactical inquisitiveness, the 3–3–1–3 is a beautiful system to explore for the understanding of superiorities and moments that lead to transition. There is very less room for error, but if every position dominates its zone individually, the outcome is fast-paced and exciting to watch. With every strength comes a weakness, and both appear quite evident in the 3–3–1–3.